The Peaking of the United States of America

- Financial Insights

- Market Insights

- US equities at 60-65% of the global equity market index look to be emphatically peaking

- The experience of the peaking of Japanese equities in late 1980’s and early 1990’s may be relevant

- Emerging markets are substantially unrepresented in global equity portfolios

- We continue with a guidance of underweighting US equities

Gary Dugan

The Global CIO Office

In meetings with many global investors last week, I was struck by the tangible change in attitude regarding US assets and the US dollar. De-dollarisation has been a part of the investment discourse for some years. However, I have never been so convinced that it has become something that has a meaningful impact on how people invest currently.

De-dollarisation refers to reducing the dollar’s dominance across global markets. Still, I would prefer to stretch the concept slightly beyond to the potential reduction by international investors in their exposure to US asset markets, particularly equities.

While institutional investors – and often asset managers, too – have religiously followed MSCI equity market benchmarks, I have never been a fan of the idea. These benchmarks guide investors to allocate – or rejig – their equity market exposure according to the weightings set by MSCI. The weightings allocated to individual markets have some intellectual merit, but at times they push money managers to extreme portfolio concentrations in just one country. Today, the MSCI global equity index assigns an almost 65% weighting to US equities alone. Replicating such a heavy weighting to US equities in a portfolio runs counter to one of the guiding principles of portfolio management, i.e., diversification.

History shows us that if investors follow the MSCI indices to their extremes of heavy weightings in ‘leading’ countries, it can eventually end in undesirable poor performance. At the peak of Japan’s economic prowess in the late 1980s, Japanese equities had a 44% weighting in the MSCI global equity index. From that peak in the late 1980s, Japan’s weighting in the global index has fallen to just 8% at present.

The history of the demise of the Japanese equity market should make one think twice about blindly following the MCSI weightings. Based on what happened to Japan and considering that the US equity market today accounts for 65% of the global index, it almost screams to sell US equities. But is such a bearish view warranted?

It will be prudent to first analyse the factors that led to the downfall of the Japanese economy and its equity market. The so-called ‘lost decade’ for Japan of the 1990s had four defining macroeconomic facets:

- A collapse in real estate and land prices

- A stop-go monetary policy

- The central bank put the brakes on money supply growth, and

- Liquidity trap -when households and corporates sit on cash

Does this sound familiar? In the backdrop of these four elements that led to the collapse of the influence that the Japanese economy and market wielded, let’s analyse the current conditions in the United States.

- Real estate under pressure in the US? A Morgan Stanley strategist was quoted as saying that US commercial real estate prices could fall 40% from their peak.

- The Fed was late in tightening the monetary policy and has been far more aggressive than the market expected it to be. A stop-go measure?

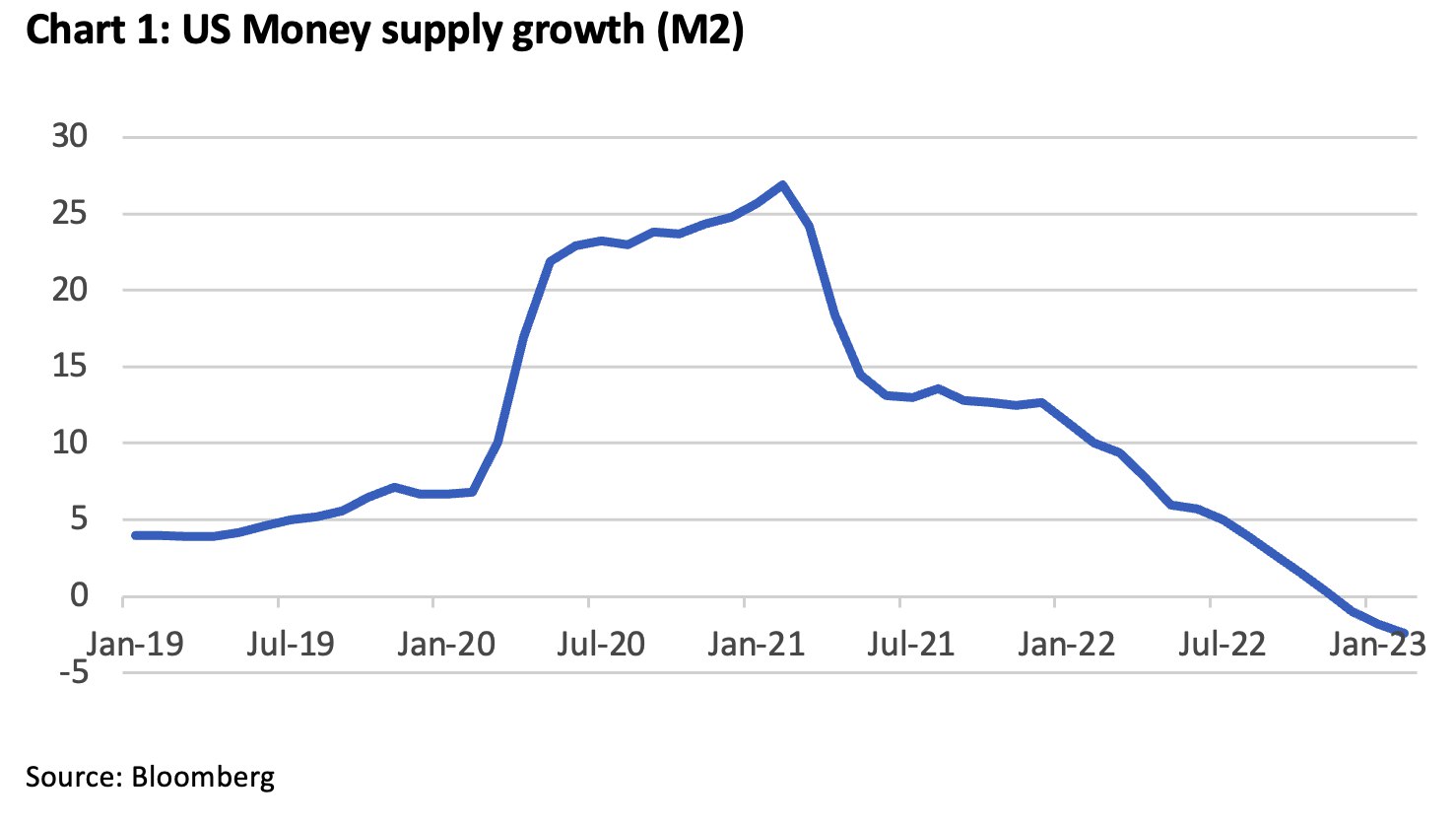

- Brakes on money supply growth? US money supply growth is collapsing, with M2 growth turning negative as the Fed fights inflation (Chart 1).

- Liquidity trap? The Fed setting short-term interest rates at 5% has encouraged householders to take their cash away from asset markets and hoard it in money market instruments. Corporations are likely to hoard cash rather than spend it for fear of the impact of the tightening monetary conditions.

The implicit waning of the US asset markets and the US economy’s dominance in the global economy could lead to a significant reassessment of the construct of global portfolios. Let’s start with a simple statistic – the US’s share of global GDP is just 16% currently while the share of emerging markets in global GDP is a staggering 45%. How do we then square these facts with how the MSCI all-country equity index allocates weightings to the US (65%) versus the emerging markets (just 11%)? Well, many US companies are global behemoths. In aggregate, on a market cap-weighted basis, 30-40% of corporate revenues come from international markets. But this only marginally closes the gap between a 65% equity weighting and a 16% share of the global GDP. Thus, the US is massively overrepresented in global indices considering the size of its economy.

The gap between the emerging market’s weighting in global indices will indeed close as international investors come to better appreciate these markets for the growth prospects they offer. The gap will close further when global investors assign a higher valuation to emerging markets. At the end of February 2023, the emerging market index traded at a historical P/E of just 12.0x versus 29.0x for the US (Source: MSCI).

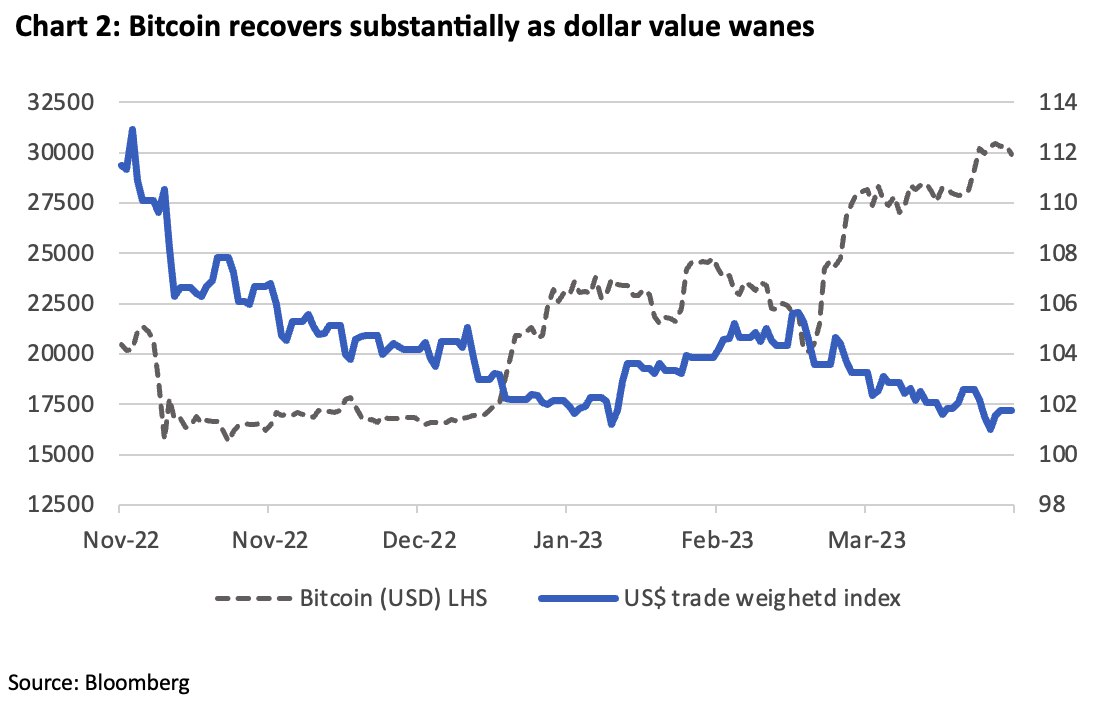

The evidence of a broader investor aversion to dollar-denominated assets is has been loud and clear in the recent fall in the US dollar trade-weighted index, which is down around 7% from its peak and has remained under pressure since (Chart 1).

The dollar’s weakness has led to a surge in gold and bitcoin prices. In fact, bitcoin’s revival from its low has been almost a complete inverse of the dollar’s weakness from November last year. Bitcoin has risen 92% from its low during this period. The cryptocurrency is nowhere near the dollar’s standing in international trade and asset markets; yet, it is a good indicator of the degree to which investors are seeking alternatives to the dollar.

Gold, the more traditional alternative when the dollar is under pressure, is up 23% since November 2022.

Chart 3: Gold price per oz

Our advice to investors should be to not have blind faith in dollar assets. Allocations to the dollar as a store of value, or as an (outsized) regional allocation for equity investment appear to be clearly on the wane. Blindly holding onto large allocations to US asset markets, particularly equities, should be a thing of the past. Japan’s experience in the 1990s of its declining economic prowess is a salutary lesson in perils of holding onto a wishful dream that the US will somehow remain insulated.