Markets still Prepared to Believe in the Good News and Ignore Inflation

- Financial Insights

- Market Insights

- Fed expected to raise rates by 25bps this week.

- Last week’s 1Q US GDP report weaker than expected but with strong elements.

- US smaller banks still in trouble

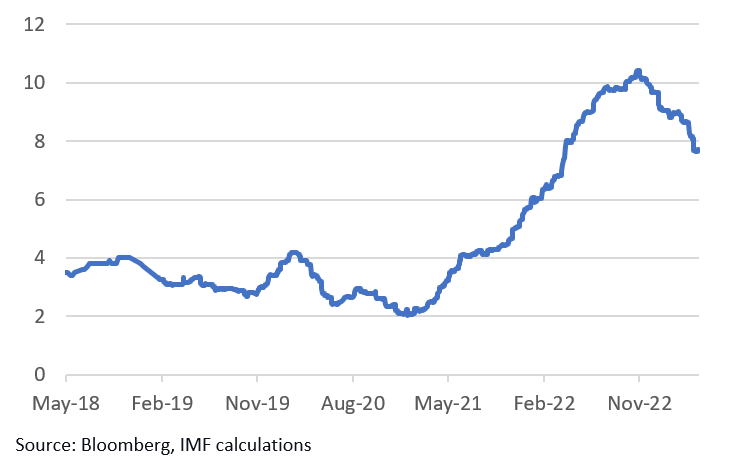

- We are still concerned with the stickiness of global inflation.

- Many central banks are likely to pause their rate hikes but may still have more to do in due course.

Gary Dugan

The Global CIO Office

The evidence from worldwide economic data is that global economic growth still seems robust. Industrial confidence indicators suggest that global growth is still holding up well, although on a weakening path. However, that weakening path at the moment is not pointing to a risk of a marked recession. Consequently, equity and bond markets have remained relatively upbeat, with equities holding on to their excellent gains since the beginning of the year.

The persistence of inflation remains a risk to global growth. Should central banks feel forced to raise interest rates still further, that could significantly increase the odds of a worldwide recession before the end of the year. However, at this stage, the market hopes that the next round of rate hikes from the major central banks will be the last before they pause their tightening.

Chart 1: UK Headline and Core Inflation

The market expects the Federal Reserve to raise their policy rate by 25bps this week and leave the door open to another rate rise in June should there be the need to act on stronger-than-expected inflation. The Fed will also be mindful of the challenges among the smaller and medium-sized banks. First Republic Bank was back in the news with worse-than-expected deposit losses leading to another collapse in its share price, down 76% on the week. The F.D.I.C. has now put the company out to tender with an auction involving many leading US banks.

The central banks of Australia and Canada are likely to keep their rates unchanged at their upcoming meetings. Still, both are likely to signal that the bias of risks is for a possible hike in interest rates rather than a cut any time soon.

The Bank of Japan has kept the markets guessing about future interest rate policy and yield curve manipulation despite the new leadership of Governor Ueda. Economists see an upside risk to inflation, which is likely to pull the central bank into some policy tightening, most likely a change to yield curve manipulation.

US equities held up well last week despite US first-quarter GDP, which on the surface looked much worse than expected. First quarter GDP growth was half of what was expected by the consensus. However, the devil was in the detail. There were some strong elements to the report, notably the strength of real consumer spending, up 3.7% quarter on quarter annualised. A negative contribution from inventories was the main reason for headline weakness – companies reduced their inventories in anticipation of weaker growth. They may now be refilling their inventories due to the strength of consumer spending. Of more concern was the drop in investment. This is the third decline in investment spending in the past four quarters.

Our abiding worry is that we must see inflation being washed out of the global economy with a marked slowdown in growth. Given the excellent momentum in global growth, higher interest rates may still need to put inflation on a path to central bank targets. A number that didn’t get the headlines but demonstrates the inflation at hand is the US employment costs index in the US which showed US wage growth at 5.0%.

No New Reign in Prospect for UK Asset Markets

A recent improvement in investor sentiment cannot disguise persistent structural weaknesses

- UK economy has rebounded from its winter freeze

- Structural challenges, though, leave the outlook quite uncertain

- UK is struggling to position itself as relevant in the global economy

- Interest rates have a bias to be higher than expected, which should help sterling

- UK equity market appears inexpensive – but does anyone care?

May 6th will see the crowning of King Charles III in London. Unfortunately, the coronation of a new monarch comes at a time when the asset markets in the UK are completely devoid of any crowning glory, even as they struggle to prove their relevance to international markets. Our UK-based CIO partner Bill O’Neill reflects on the developments.

Spring-time optimism after the winter freeze….

The UK economy seems to have hauled itself up quite a bit from the mid-winter despondency. The decline in energy prices and a resilient labour market have staved off the risks of a lengthy recession predicted by the Bank of England only late last year. Indeed, the latest business sentiment indicators signal momentum in growth, which is further buoyed by a robust service sector. The flash UK composite purchasing managers’ index rose to 53.9 in April, up from 52.2 in March, signalling a revival in business activity. Consumer confidence looks to have turned a corner, too, with the GfK conumer confidence index rising by six points to -30 this month, beating market expectations of a reading of -35.

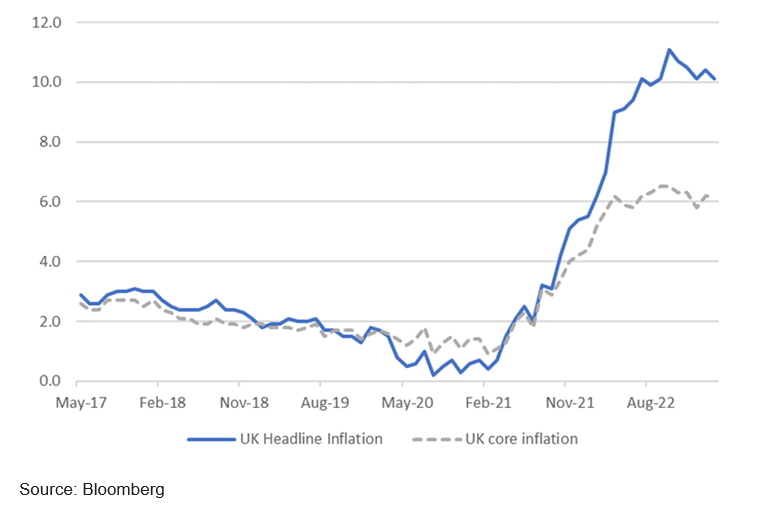

However, the story of UK consumer price inflation is much more nuanced. Unlike in other G7 economies, headline CPI inflation in the UK remains stuck at 10.1%, as of March. The inflation scenario, though, is likely to improve sharply over April and May as the base effects kick in, thanks also to the retail energy price cap. Food price inflation, too, must inevitably fall back from its current eye-watering level, although price gouging is a concern in this sector. At just above 6% per annum, UK core inflation is barely ahead of the eurozone’s 5.7% and comparable with 5.6% in the US.

Chart 2: UK Headline and Core Inflation

…but structural obstacles to higher GDP growth and lower inflation remain embedded in the system

The broad macroeconomic outlook is still unimpressive. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in the March edition of its Outlook predicted GDP to contract 0.2% in 2023 (the weakest in G7) before growth accelerates to 1.8% in 2024. The key driver of the weakness is the slump in household real disposable and private (especially inward) investment. The Bank of England in February forecast that the level of GDP is not expected to reach the pre-COVID levels until 2026.

Nonetheless, as a likely change in government appears on the horizon, UK macroeconomic challenges increasingly focus on the weakness of its underlying growth rate both in terms of a labour market expansion and worker productivity. A myriad of factors have been quoted, such as

- A sclerotic, inconsistent planning process wedded to political interests.

- The permanently negative post-Brexit impact because of trade frictions with EU and disincentives towards inward capex.

- A regional development strategy whereby moves to decentralise economic activity might potentially enhance total factor productivity, but something that is now rapidly slipping off the government’s agenda.

- A skewed educational system not effectively aligned with an industrial strategy.

- A rising broader tax burden with the perception (at least) of increasing taxes on corporate profits. The OBR forecasts that from 2025 the government will take in about 35% of GDP in taxes, the second-highest level since the World War II.

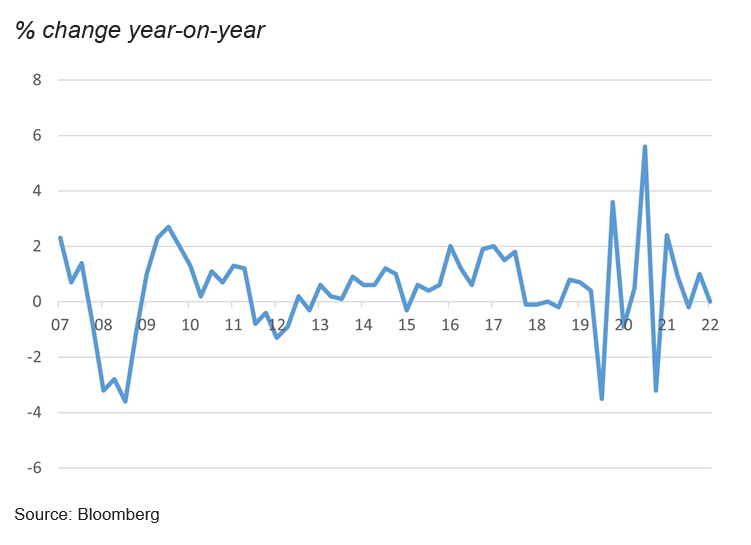

- Underlying growth in labour productivity at a paltry 0.8% p.a. accompanied by a significant shrinkage in the size of the labour force, and higher levels of inactivity post the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In sum, underlying trend growth in output continues to decline – at 1.5% today from 1.7% pre-pandemic and 2.5% pre-2008.

Chart 3: Unimpressive UK Labour Productivity Growth

Result: Policymakers confronted with minimal visibility on medium-term trends

Policy makers – both on the fiscal and monetary fronts – are therefore up against an unenviable set of medium-term drivers as they look to balance support for growth with the need to bear down on core inflation over the longer term. Fiscal policy is still overshadowed by the trauma of the Liz Truss administration’s mini-budget presented last September. Market confidence has since stabilised, of course. Yet, with demography-led upward pressure on health and social spending and HM Treasury’s commitment to see the government’s debt burden decline from five years out, the scope for any fiscal support for the economy is highly limited at this juncture.

The key structural concern for the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is the state of the labour market and, in particular, the shrinkage in supply. If inactivity persists and immigration flows become again mired in political slugfest, resulting in a persistently tight labour market, the ability of the economy to grow by even 1.5% p.a. without sparking a resulting inflation will be called into doubt.

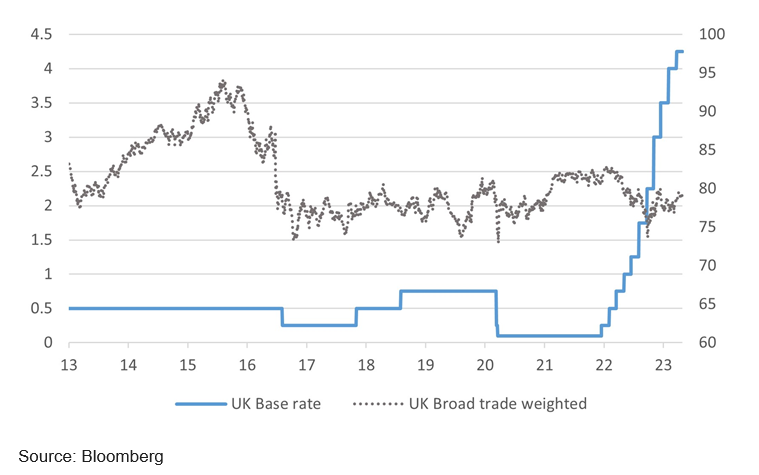

Chart 4: Bank of England Refi Rate and Sterling Effective Exchange Rate

Most economists still expect the headline inflation rate to ease to just above 3% by December this year. The larger worry for the MPC is the challenge in forcing the underlying rate back to its targeted range of close to 2% p.a. The policy interest rate will almost certainly be hiked to 4.5% at the MPC’s May 11th meeting. The hot UK labour market, captured in an underlying growth in average earnings of 6.6% p.a., is still uncomfortably high to get close to what might be consistent with a 2% p.a. inflation over the medium term. So, it wouldn’t be a surprise if a move beyond a 5% peak in rates (as currently priced by the market at year end) isn’t soon perceived as a possibility – offering more support to a still ’cheap’ sterling over the summer months.

UK asset markets risk moving to a ‘back water’ for international investors

Investors can draw comfort from the fact that sterling in 2023 can benefit further from higher interest rates when compared to developments in other G7 economies with an easing in the pressure on household finances as energy prices decline.

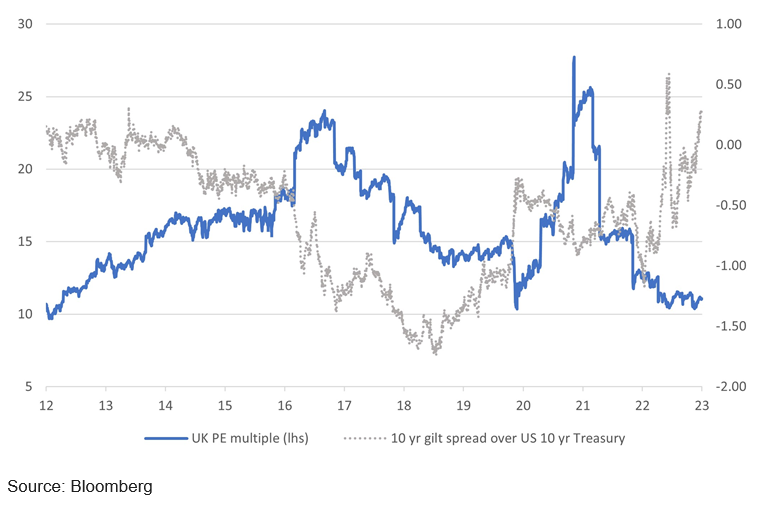

Chart 5: UK 10 Year Treasury Gilt Yield vs. US Treasuries and Forward P/E of FTSE100

UK asset classes are at risk of becomign increasingly irrelevant to global investors. While the UK equity market includes some global brand names, it per se offers little in terms of a story. Indeed, last time the flash crash of the gilt market and a change in prime minister presented a rather unimpressive ‘story’ in UK asset markets. Nevertheless, the equity market does still offer value at a current P/E multiple that is close to the lows of the past decade. Moreover, it offers diversification versus a holding in the US equity market with a correlation of 0.56 to daily returns in USD over the past year.

Yet, the more concerning theme is international investors shying away from UK asset markets. This has been evident in the London Stock Exchange for some time with de-listings threatened and enacted – ARM being a recent example – on the premise that tighter regulations and a limited domestic investor base deter offshore companies seeking an appropriate platform for raising funds. According to the Economist, London accounted for less than 1% of the capital raised through global initial public offerings last year, compared with 18% in 2006. The UK stock market now only accounts for just 4% of the total global equity market capitalisation. The gilts market is similarly under pressure as key long-term buyers such as defined-benefit pension funds and the Bank of England go into retreat threatening to transform a ‘moron premium’ in gilt yields vs. G7 counterparts into one reflecting a fragmented buyer base.