Central Bankers Attempt to Climb Out of a Hole

- Financial Insights

- Market Insights

- Central bankers signal higher for longer, but watching the data

- ECB Lagarde refers to a “new playbook”

- BRICS broadens, underlining the profound change in the power of the so-called emerging markets

- China still struggles to placate the ongoing angst among investors

- China’s political thought at odds with capitalist financial markets

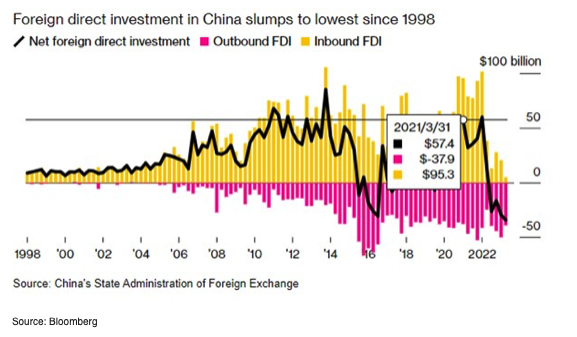

- FDI flows to China remain at risk

Gary Dugan, Chadi Farah, Bill O'Neill

The Global CIO Office

Few surprises emerged from the foothills of the Teton Range in Jackson Hole last week. For some time now, it has been evident that policy makers are still concerned about the persisting inflation and the signs of a re-acceleration in growth in the United States. Thus, while central bankers in the US remain biased – perhaps reluctantly – towards further rate hikes, the markets believe differently, ascribing just a 40% probability of a Fed rate hike by year-end. ECB President Lagarde, speaking at the annual symposium, was rather candid in her admission of the goings-on, articulating that “there is no pre-existing playbook for the situation we are facing today – and so our task is to draw up a new one”. Roughly translated, central bankers are living from meeting to meeting. The Fed has admitted as much with its focus on data watching.

Bond yields were generally lower on the week, with bond prices recovering from the previous week’s angst-filled sell-off. Shorter-dated bonds did suffer a modest sell-off with the US two-year Treasury yield rising to a multi-year high of 5.09%.

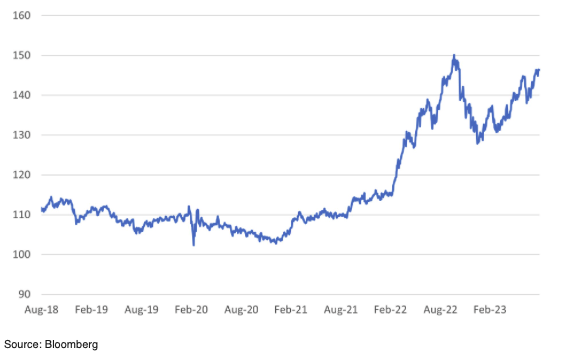

The Fed’s hawkish posturing is in contrast with the Bank of Japan’s reticence to admit that it is making progress in re-establishing sufficient inflation in the economy. The JPY/USD at 146 should warrant intervention from the Bank of Japan. In the fourth quarter of 2022, the JPY/USD peaked at 150.

Chart 1: JPY to USD spiking back to limit of Yen weakness

A Broader BRICS—Stronger, too?

In a somewhat surprise move last week, the BRICS nations decided to expand the bloc from the original five of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa to include Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. There were widespread expectations that India would block the move on apprehensions that any such expansion would increase the influence of China in the emerging market bloc. That didn’t happen though. Meanwhile, Indonesia, although initially invited, declined to attend, still seemingly uncertain of its ambition for bilateral trade with China. It is an agreement in principle, so it is not instituted at this stage.

The inclusion of the UAE and Saudi Arabia into the bloc puts more capital at work in the group as the net surpluses of the Middle East can be put to good work on opportunities now afforded by the closer cooperation amongst the major BRICS countries. The move is another step in Iran and Egypt’s reintegration into the international community. The developments particularly help the UAE in its ambition to provide the pre-eminent East-West Hub between Asia and Africa.

BRICS, including the new inductees, account for 37% of the global GDP, up from 31.5%, in terms of purchasing power parity, which would be more significant than G7, which is at 30.7%.

China – don’t forget the political fundamentals

We increasingly believe that the Chinese authorities will not even pay lip service to the needs of Western investors. While the world at large keeps waiting for China to address the issues severely plaguing its economy, the authorities have yet to announce any compelling set of measure that would calm the sentiments and reassure the markets. We increasingly believe that the ‘big bazooka’ is not coming. Instead, we are challenging our hopes – aren’t these just built on sand? We must concede that the country has become what its leadership wants it to be – a centrally planned economy with the control firmly in the hands of the communist party and, in particular, its leader Xi Jinping.

In early 2020, when China’s pre-eminent entrepreneur, Jack Ma, was leading the charge of China’s economic might with the pending float of And Financial, everything looked so different. China, with the idea of “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” looked like an attractive country to invest in. However, by November of that year, as Jack Ma was ushered away from the centre stage, the writing was clearly on the wall that China was on a path to re-adopting a brand of political philosophy that would prove difficult – if not outright alien – to Western investors. Let us remind ourselves of the building blocks of the country’s political philosophy:

- China is governed by a Marxist-Leninist ideology. A Marxist-Leninist system aims to transition from capitalism to socialism with the goal of achieving communism. Socialism involves collective ownership and control of the means of production, where the state or the working class takes control of key industries and resources.

- In a Marxist-Leninist system, the state typically owns the major means of production, such as factories, land, and natural resources. This is intended to prevent the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few individuals or private entities.

- In the Marxist-Leninist ideology, the relationship with the rest of the world takes on a very different form. It promotes international solidarity among working-class movements and can encourage the spread of socialist revolution across borders. This perspective envisions a global transition to communism and eliminating nation-states.

Since the start of this year, names such as Marx, Lenin, Mao, and Deng have all but disappeared from China’s political rule book. Instead, the emphasis increasingly has been on the thoughts and ideas of Xi Jinping as he starts his third and indefinite term in office. Also, China’s political rulebook vested executive power in the hands of the Communist Party working groups and away from government ministers.

While our intent is not to judge the merits or demerits of a political system over another, we can judge whether a political system is palatable to global investors.

To its credit, the Chinese leadership is trying to evolve its economy away from significant reliance on the real estate sector and debt for growth. However, we suspect that global investors will not be confident that a centrally planned economy is the best system to effect such a change.

The only caveat is that we do not expect the authorities to remain rigid and not change policy meaningfully when the party’s authority is questioned. The authorities made radical policy shifts when the protests over the COVID lockdowns seemed to unnerve the leadership. However, the re-opening is believed to have led to a sharp increase in mortality over the following six months. No wonder that household consumer confidence is still taking time to recover.

Over the weekend the authorities have announced a reduction in stamp duty on equity trades. These, in our view are all incremental policy shifts that we believe will have limited impact in reversing the current downtrend in Chinese asset prices.