- Financial Insights

- Market Insights

Are You Ready for Liberation?

Gary Dugan, Chadi Farah, Bill O'Neill

The Global CIO Office

This week, I was reminded by my former JPMorgan colleague, Tim Harris, that it’s now the 25th anniversary of the tech wreck of 2000. That anniversary stirred memories of a pivotal moment in my career—just over 25 years ago, in February 2000, I stood on Wall Street addressing the International Advisory Board of JPMorgan. In a rather bold move, I gave the board five minutes to call their brokers and sell all of their stocks. I forecast that the US equity market would fall by 50% and warned that the tech sector was headed for a major crash.

It was a remarkable audience. The Board was chaired by the late George Shultz, and among those in attendance were Lee Kuan Yew, Sir Geoffrey Howe, JPM CEO Sandy Warner, and about twenty captains of industry from across Europe and the US.

After my presentation, one board member—who shall remain nameless—pulled me aside and said, “I agreed with everything you said, Gary, but I didn’t want to say it in front of everyone else.”

Now, 25 years on, I can’t help but wonder if we’re living through another one of those moments—when the risks are clear, but too few are willing to speak up.

Are You Ready for Liberation?

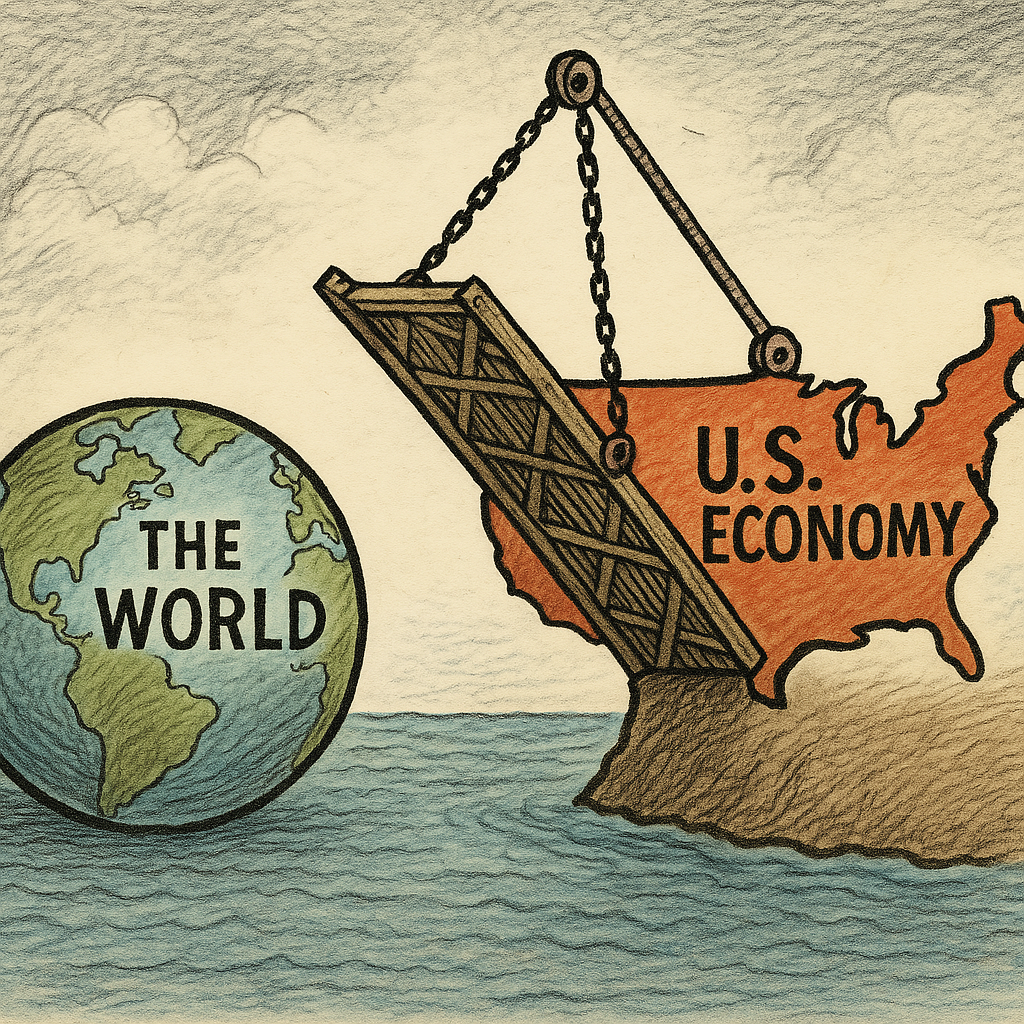

The world is watching with bated breath as US President Donald Trump prepares to unveil what he calls “Liberation Day”—a sweeping package of new tariffs aimed at “reshaping America’s trade relationships”. While the full details are still sketchy, the buildup to this announcement has already had a chilling effect on sentiments. Industrial and consumer confidence is declining, not only in the United States but globally, but, crucially, the ripple effects extend far beyond specific industries or sectors—supply chains are being disrupted, and long-term corporate planning is being thrown into disarray.

There is little comfort to be found in the prospect—and the consequences—of the world’s largest economy engaging in what is evidently a trade war with much of the rest of the globe.

What’s striking at this juncture is how underappreciated these shifts in policy seem to be by investors. For decades, the global economy has operated on the principles of relatively free trade and open flow of goods, services, and labour. That era is rapidly changing. The US, long seen as a champion of globalisation, appears to be pulling up the drawbridge.

The shift is as much philosophical as it is economic. The United States —“the land of the free,” as Francis Scott Key chose to call it in his poem “The Star-Spangled Banner—is turning inward, doubling down on Trump’s “America First” agenda. It was this narrative that helped catapult the current political leadership to power, but one that comes at a cost: strained international relationships and growing economic friction.

Markets: Pricing in Uncertainty

While uncertainties persist, markets have so far remained relatively resilient—at least until the latter part of last week—trading within what might be considered a normal range. This stability may be underpinned by a mix of short-term optimism and long-term denial. However, beneath the surface, volatility measures are beginning to rise, and globally exposed sectors—particularly industrials and technology—are starting to show signs of strain.

Fixed income markets may become increasingly sensitive to geopolitical shifts. Tariffs are, in effect, a tax on consumers and a potential source of inflation. The bond market may start to reprice inflation expectations and central bank policies if protectionist measures accelerate.

Meanwhile, the dollar’s role as a global reserve currency could be under pressure if US policy becomes more unpredictable and less cooperative internationally.

Corporate America: Strategic Paralysis?

Perhaps the most under-discussed impact of this shift is on corporate behaviour. For US multinationals, the challenge is profound. For instance, how does a company build a 10-year supply chain strategy when the rules of trade may change every four years? Or, how does a global brand manage reputation and customer loyalty when tariffs or executive orders can isolate foreign markets overnight?

The uncertainty around future policy direction—particularly given the radical nature of the administration’s proposals and the limited four-year window of a presidential term—is forcing US firms into an awkward balancing act. Do they double down on domestic investment, or maintain global diversification? Should they hedge against political risk by relocating operations or adjusting pricing models?

Boardrooms are increasingly being forced to weigh not just economic and competitive factors, but political ideology and geopolitical realignment. That’s a tall order in any environment—and even more so when the next presidential election could reverse course once again.

A New Era, Ready or Not

The global economic framework that has defined the past generation is being reshaped—not by war or technology, but by political will. Investors and companies alike must now grapple with a world where certainty is scarce and where ideology—or the lack of it—is becoming a key market driver.

It’s not just about whether you’re ready for “Liberation Day.” The bigger question may be: are you ready for a different kind of world order?

Stagflation May Be the New Norm

Among economists, there’s a growing sense of resignation that the next few quarters could be particularly challenging, marked by a toxic mix of slowing growth and stubborn inflation. The reality is hard to ignore: the global economy appears increasingly vulnerable to a period of stagflation, a scenario not seriously contemplated since the 1970s but now featuring in conversations with uncomfortable regularity.

Inflation expectations are flashing warning signs. The US two-year breakeven rate—reflecting the market’s expectation for average inflation over the next two years—has surged to 3.27%. That’s not just elevated; it’s among the highest levels since the early stages of the pandemic, when supply chains were in disarray and stimulus cheques were fuelling a demand spike. For comparison, the 10-year breakeven sits closer to 2.3%, suggesting markets believe the short-term inflation pulse is more problematic than the long-term trend—an inversion that has historically preceded economic slowdowns.

Chart 1: US Bond Two-Year Breakeven (%)

Source: Bloomberg

Despite this, some investors remain anchored to the idea that current economic conditions are resilient. Recent data points such as the US Q4 GDP growth at 3.2% and stronger-than-expected payroll numbers have created an illusion of strength. However, beneath the surface, cracks are emerging.

For one, much of the recent growth has been artificially front-loaded. Companies have accelerated inventory purchases amid lingering fears of supply chain disruptions and geopolitical tensions, notably in the Red Sea and Eastern Europe. Retailers and manufacturers alike have filled warehouses—not necessarily because demand is strong, but out of precaution. Inventory-to-sales ratios have climbed sharply, particularly in durable goods and wholesale trade. The risk now is that demand falters while supply sits idle—classic conditions for margin compression and layoffs.

Meanwhile, the consumer is finally starting to show signs of fatigue. Delinquency rates on credit cards have risen to 3.1%, their highest level since 2012. Real disposable income has stagnated, and consumer confidence, as measured by the University of Michigan survey, remains well below pre-pandemic averages.

All this plays out against a backdrop of geopolitical uncertainty and a central bank boxed in by policy constraints. The Fed’s hoped-for “immaculate disinflation” is increasingly at risk of becoming a pipe dream. If inflation remains sticky while growth fades, the Fed may find itself unable to ease meaningfully without reigniting price pressures—hence the risk of stagflation becoming more than just a theoretical concern.

In short, we may not be at the cliff edge yet, but the warning signs are mounting. The bond market sees it, the consumer feels it, and corporate America is bracing for it. It might just be time investors do, too.

Sector Views in a Stagflationary World

If stagflation—defined as rising inflation with slowing growth—does take hold, the traditional playbook for investing needs to adapt accordingly. Here’s how sectors may fare:

1. Energy

- Why: Energy often holds up well during inflationary periods, particularly when inflation is commodity-driven. Oil and gas companies’ profitability benefit directly from higher input prices.

- Current Colour: Hedge funds have increased their bullish bets of late on the assumption that President Trump will constrain the access of Iran and Venezuela to the global oil markets and that OPEC will maintain its discipline of production.

2. Utilities

- Why: Seen as defensive due to stable cash flows and inelastic demand. During periods of stagflation, they act as volatility dampeners.

- Caveat: Rising real yields can be a headwind due to utilities bond-proxy nature.

- Look For: Regulated utilities with inflation-linked pricing mechanisms and minimal debt roll-over risk.

3. Precious Metals/Gold Miners

- Why: Gold is historically a safe-haven during periods of policy uncertainty and real rate compression.

- Current Colour: Gold is trading at record highs (~$3085/oz), despite higher nominal yields

- Trade Angle: Consider gold miners with operational leverage to rising gold prices but strong cost control.

Under Pressure

1. Consumer Discretionary

- Why: These stocks are most exposed to the weakening consumer and margin pressure from rising input costs.

- Evidence: Inventory builds across retail (especially apparel, home goods) are raising red flags. Credit card delinquencies are also ticking up.

- Sub-sectors to Watch: Lower-end retail, e-commerce, automotive.

2. Industrials/Cyclicals

- Why: Slowing demand coupled with rising labour and input costs compress margins. Companies with global exposure face added FX and geopolitical risks.

- Current Colour: Freight volumes are slowing, and new orders in PMIs have softened globally.

3. Financials (Selective)

- Why: Higher rates are good—until they’re not. Credit risk is rising, yield curve remains inverted, and loan demand is softening.

- Watch: Regional banks with high exposure to commercial real estate and overleveraged consumers.

Neutral to Mixed

1. Healthcare

- Why: Defensive in nature, but cost pressures and political headwinds (e.g., drug pricing reform) could offset stability. And investors have always been aware of slippage on drug pipelines – Novo Nordisk is down 55% in the past nine months due to delays on its anti-obesity drug.

- Best Bets: Large-cap pharma and medical equipment companies with global diversification and pricing power.

2. Technology

- Why: Typically hurt by rising rates and lower growth. However, AI-driven demand offers a unique offset, making this cycle less conventional.

- Split View: Mega-cap tech with fortress balance sheets may still outperform broader tech, especially semis with AI exposure.

- Risk: Overcrowding. The “Magnificent Seven” have made up more than 30% of the S&P 500 by market capitalisation.