Testing Times

- Market Insights

- Financial Insights

- US inflation better, but not comfortably reverting to the Fed target

- Market appears too optimistic in expecting Fed rate cuts early next year

- Remember US growth forecasts are rising and the labour market remains tight

- China’s economic challenges deepen with more trouble in the real estate sector

- Italy makes a hash of fiscal tightening

Gary Dugan, Chadi Farah, Bill O'Neill

The Global CIO Office

Some economists drew comfort from last week’s US inflation report, but we believe it still does not paint a rosy picture. Core inflation, which peaked at 6.6% year-on-year last September, is still at 4.7%, indicating it remains sticky and high. We continue to be sceptical that the US Federal Reserve will be in a position to cut interest rates through much of the next year absent a global event that brings about a marked slowdown in growth. The market is currently pricing Fed rate cuts from as early as March next year. In our view, a rate cut is not likely at least until late 2024.

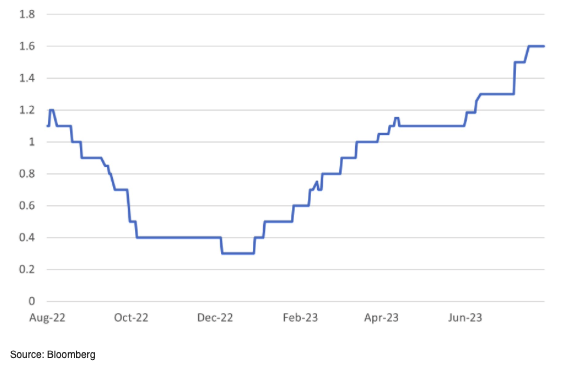

US growth, we believe, is too robust and hence inflation risks remain to the upside. That’s not to say that inflation will re-accelerate to a higher number, but in all likelihood it will stay around the 3-4% level. A still very tight labour market and what appears to be a re-acceleration in growth all add to upside risks to inflation. This week should see retail sales re-accelerate to around a 0.6% month-on-month growth. Quietly, in the background, economists have continued to revise up their US GDP forecasts for 2023. The consensus forecasts have since inched up to 1.60%, compared to a forecast of 1.1% in the middle of the year. Second half growth alone is now expected to be approximately 2.0%.

Chart 1: Consensus Forecast for US GDP Growth – 2023

China – deepening woes

The Chinese economy continues to throw up unwanted surprises. There have been moments of occasional exuberance, but that aside, the economic news flow in China continues to steadily deteriorate. In late-Saturday filings with the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, Country Garden, Chinese property sector heavyweight, suspended trading in 11 onshore bonds issued by the company and its subsidiaries. Country Garden, which relies heavily on buyers’ pre-payments for its funding needs, has struggled for much of this year to build up its finances. With a 75% drop in sales from 2021 levels, it has found it difficult to make the maths work for it. In late-July, the company abruptly shelved an equity issue, and it now faces the real prospect of bankruptcy. It is somewhat baffling how fortunes have turned for Country Garden. Over 2018 to 2021, the company notched up some remarkable growth to become China’s biggest developer!

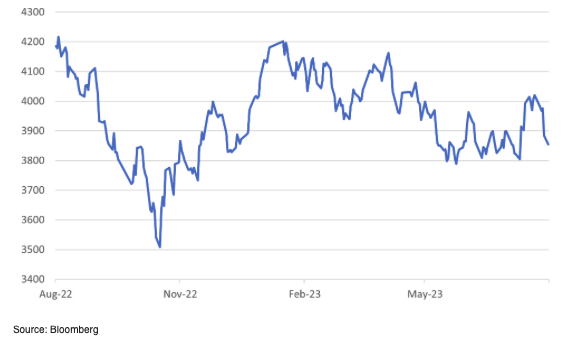

Perhaps we, like many investors, have been too optimistic in believing that Chinese authorities will institute some measures to fix the economic malaise plaguing the country’s economy. As we have often said, if China wants to play in the global financial markets it has to play by the rules. There has been some acknowledgement of the challenges facing the economy but the incremental policymaking by the PBoC, the Chinese central bank, has proved to be insufficient in stemming the tide of bad news. We sense that it will take real political pressure from within the Communist Party for there to be a real change to emerge. Something akin to the rapid about face on the COVID lockdowns is needed to stabilise the financial markets. In the absence of some comforting news, we suspect the market is at risk of going back to its October 2022 lows.

Chart 2: Shenzhen 300 Equity Index

Italy’s tax swipe on bank profits – a sign of mounting pressure on public budgets

The Italian government surprised markets last week with a proposal of a one-off 40% windfall tax on banks’ earnings from the margin between lending and deposit rates, in response to the latter’s perceived unwillingness to pass on higher interest rates to its customers. The muddle and confusion around the policy introduction is seen in the subsequent volte-face by the government in reaction to the resulting sell-off in bank shares. A day after the announcement, the government adjusted the tax to be capped at 0.1% of total assets. The move follows similar tax levies in Spain, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Lithuania over the last year. Such taxes have a way of being repeated and there is no evidence that they force banks to pass though rate hikes to depositors any more quickly.

Although the bank shares rebounded, the episode further damaged Italy and the Meloni government’s international standing. And this could not have come at a worse time considering Rome is grappling with higher funding costs on a government debt burden that has skyrocketed to 144% of GDP (2022). It underlines the quandary all eurozone governments face in their need to narrow high budget deficits post pandemic and the Ukraine war spending and in response to European Commission (EC) requirements.

According to EC, the projected Italian budget deficit is expected to be 4.5% of GDP in 2023 before it improves to 3.7% of GDP in 2024 as the energy support measures are completely phased out. The risk of stagflation and higher interest costs next year clearly make this forecast doubtful. With an acute sensitivity to the march of populist movements of late, austerity is not an option in paying for a variety of consumer support programmes. Higher taxes on wealth, business, and non-earned income are most definitely on the table.

Beyond deterring investor interest in bank equity, one other factor should keep the Italian political class awake at night – its dismal record in attracting foreign direct investment. In the last decade, Italy’s net foreign direct investment into the country stood at a paltry 0.84% of GDP per annum. The comparable figure for the euro area is 3%.